He Came Upon an Iron Horse and Prosperity Followed

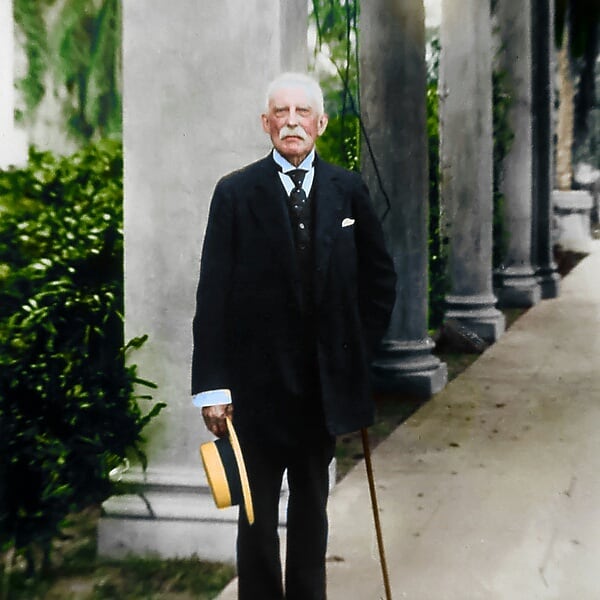

Tycoons. Robber Barons. Conquer Capitalists. Every American era bears the indelible marks of those seemingly built to succeed within the up for grabs world of the free market. They are simultaneously hated and admired, condemned and praised. Regardless of opinion, they define the world around them. All built financial empires. A portion of those built communities, schools, churches, or parks as well. Henry Morrison Flagler dedicated the last thirty years of his life, as well as half of his fortune, to building an entire state. Florida’s emergence from swampy backwater to the tourist icon that it is today is due to the daring, persistence, and generosity of a single man.

The Boarding Platform

Henry Morrison Flagler was born January 2nd, 1830 to Reverend Isaac Flagler and Elizabeth Ann Caldwell Harkness. The Flagler family, originally spelled Flegler, hailed from the southwestern corner of Germany known as the Palatinate region. The family being of moderate means, Henry struck out from New York to Republic, Ohio in 1844. It was a small town of roughly 1,000 individuals, but familial connections led to a job at a general store. His talent and work ethic blossomed, and he turned a $5 a month job in $12 a month within ten months. It was the beginning of a financial success thread that would run the length of his life.

A few changes of scenery found Henry in Bellevue, Ohio working for the Harkness side of his family in the mercantile business. By 1852 he had become a partner and expanded the business to include grain trade. It was during this period that he married his first wife, Mary, daughter of Mr. Harkness, and became acquainted with a man destined to play a leading role within his life, John D. Rockefeller.

Dedication, creativity, and foresight marked the steady rise of Henry’s professional life. However, the 1860 salt strike led to his only failure as a businessman. He made his way to Saginaw, Michigan and found himself within an industry requiring intimate knowledge and skill which he did not possess. This risk ended in debt which would require a few years to overcome. But overcome he would.

All Aboard

In 1867, he joined the partnership of Rockefeller and Andrews and immersed himself in the oil business. His was the domain of transportation. Pennsylvanian oil was shipped to Cleveland to be refined and then hauled further down the line to New York to be sold. Flagler was adept at arranging favorable deals with the railroads, even to the extent of levying taxes against competing oil refineries when they used the railroads. These taxes were paid to Standard Oil unbeknownst to the competitors.

Shrewd would be an apt description of Flagler. Cutthroat, as his crowd was often labeled, would not. He simply made the best business decisions for his firm. And, at times, for others. Flagler was fond of a specific German bakery in Cleveland, the owner of which sold the bakery to try his hand at the oil refining business. Upon discovering this tidbit of information, Flagler bought the refinery from the German. Rather than merely hand over the money for the refinery, Flagler gave something of his far more valuable; financial advice. The German allotted a portion of the money to relieve debts, but took the rest in stock of Standard Oil, along with a position within the company. His salary grew to $8,000 a year as he climbed to superintendent and his stock boomed from $2,500 to $50,000. That’s a lot of brot!

The Train Kept a’Rollin’

The winter of 1883-84 introduced Flagler to Florida, a relationship within which both were reborn. At this time, Florida was a spot visited by the northeastern high society and recommended by doctors to alleviate pulmonary disorders. To arrive in St. Augustine, which is where Flagler passed his first visitation, required a train, a cab, a ferry, a cab, a train, and another cab. To elucidate further, that process simply described the Jacksonville to St. Augustine stretch. However, Flagler saw immense potential.

A fortune had already been made. Enough wood was in the shed to keep generations warm. However, at age 53, Flagler embarked on an odyssey few would dare. He knew the heart of the matter was access. Make the trip to Florida less complicated, and its natural abundance would sell itself. A narrow-gauge line between Jacksonville and St Augustine existed, but it was incompatible with the larger gauge lines spawning across the country. When the owners wouldn’t heed his advice to make the necessary changes, Flagler bought the line and made the changes himself. It was now one simple ride from the northeastern commerce hubs to St Augustine.

The enigmatic, scenic city of St Augustine had grandeur enough to entice a visitation from the yanks up north, but Flagler felt the visitors needed a dwelling equal to the uniqueness of its historical setting. Andrew Anderson agreed. He and Flagler made acquaintance in the winter of 1884-85. Anderson, a Princeton grad, believed adamantly in the potential of his hometown. Together, they gave birth to the concept of the Ponce de Leon hotel. Flagler delegated the local details to Anderson and returned north.

Flagler was an innovator in the business world. His intelligence and creativity led him to build a financial empire that is still reigns today. The Ponce de Leon, however, was not business. It was art. He selected two nascent architects to bring classic grandeur and eloquence to the resurrection of the nation’s oldest city. Thomas Hastings and John Carrere both studied at Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Thomas was born in New York. John in Rio de Janeiro. They had a perfectly suited blend of classical training with new world innovation to deliver the masterpiece which Flagler envisioned. He shipped them off to Spain. The roots of their inspiration needed to draw their sustenance from the original source. The young architects remained faithful to the coquina shell concrete and hanging balconies traditional of St Augustine, the rotundas and frescos of Europe, and infused new electric lighting to make the hotel simultaneously an ode to the past and a beacon of the future.

After the Ponce de Leon, Alcazar, and the Cordova in St Augustine, Flagler pressed southward to build hotels in Ormond and Palm Beach. Ever the diversified venture capitalist, he began a steamer service along the Halifax river which gave easier access to northern markets for the citrus industry. A stronger economy would give rise to a more vibrant community, thus strengthening the appeal of his next luxurious hotel. Or were his intentions driven by a different motive?

On the shores of Lake Worth in Palm Beach, the Royal Poinciana was constructed. A sprawling wonder of its time, the hotel accommodated two thousand guests, stood six stories high, and sat upon thirty-two acres. It was during the construction of the Royal Poinciana that another interesting insight into the mind and heart of Flagler was presented. The winter of 1894-95 brought with it a freeze that devastated the local crops. Sensitive to the cries of the resident farmers, Flagler came to their aid financially. Intrigued, he sent his man James E. Ingram south to survey the extent of the freeze. Ingram discovered crops entirely untouched. He returned from Miami with an invitation from Mrs. Julia D Tuttle beckoning Flagler to put his resources to work along the shores Biscayne Bay. Never an idol man, the railroad pushed southward.

Southbound to Swamptown

While the north of Florida displayed Flagler’s good taste, the south of the state showcased his grit and breadth of vision. In Miami, he went far beyond building a sole hotel. He laid out streets, built water works, an electric light plant, as well as home for the workers. All of which allowed the population of Miami to triple within four years of Flagler’s arrival. It is no overstatement to say that he gave Miami its start. Where the mainland ends, however, Flagler’s imagination set sail.

In a southwestern arc, the Florida Keys adventure into the divide between the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico for approximately 128 miles. It was through these Florida Straits that Flagler was at his most daring. The Panama Canal had just been completed. Key West provided the deepest port south of Norfolk, Virginia. If the Keys could be bridged, trade via the Panama Canal would make Key West the southern hub of international commerce. It was under the influence of this dream that Flagler and his men braved numerous difficulties and overcame various setbacks.

The undertaking was immense. Coastal waters were not only bridged, but dredged, as well, to the tune of 75 miles of bridges and 49 miles of dredging. Concrete was mixed on barges then placed into position via boom derricks. Supplies, including water and food, were brought from the mainland to the floating camps in which the laborers lived. One can imagine the scene being as absurd as the endeavor was daring. A total of four hurricanes hit, claiming 130 lives, but after eight years of construction the first passenger train arrived January 22nd, 1912 in Key West.

The Flagler namesakes within the state of Florida include a museum, a university, a beach, and a county, amongst countless others. Such homage was well earned. Flagler’s expenditures within the state declare why. The hotels collectively racked up a $12 million-dollar tab. The railroad system to Homestead tallied another cool $18 million, while the Key West extension alone bore a $20 million-dollar hole in the man’s pocket. $50 million in total! Meanwhile, his estate was valued at $100 million. Whether you believe his investment to have been of a business, legacy, or altruistic nature, the fact remains that Florida owes much to tycoon who began his professional life as a five dollar a month store clerk.

The end came quickly. Flagler died in May 20th, 1913 after a brief illness. It is difficult to believe that a man who island hopped upon an iron horse died of anything but his own accord. Flagler could have done no less than relinquish the grip upon one life to heed the call of the boundless possibilities beckoning from the unknown beyond.

Sources:

- Martin, S Walter, Henry Morrison Flalger, The Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 25, No 3, Jan 1947

- Corliss, Carlton J, Henry M Flagler, The Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 38, No 3, Jan 1960

- Henry M Flagler’s Hotel Ponce de Leon, Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts, Vol 23, Florida Theme Issue, 1998

- Corliss, Carlton J, Henry M Flagler Railroad Builder, The Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 38, No 3, Jan 1960

- Main Image: Historic Image of the Ponce de Leon Hotel Photo credits: @oldlives on Instagram